Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit (1807) tackles the question of experience. Not ordinary experience but dialectical experience in our pursuit of absolute knowledge. The Introduction is simply a short preliminary conception, only justifiable by going through the entire book. By searching section by section, digging into the text, contemplating and re-contemplating, discovering and re-discovering, can we understand Hegel (and any book) to the fullest in a dialectical sense?

But look… still we have to start somewhere. So here’s an attempt of an introduction to the Introduction of the Phenomenology of Spirit.

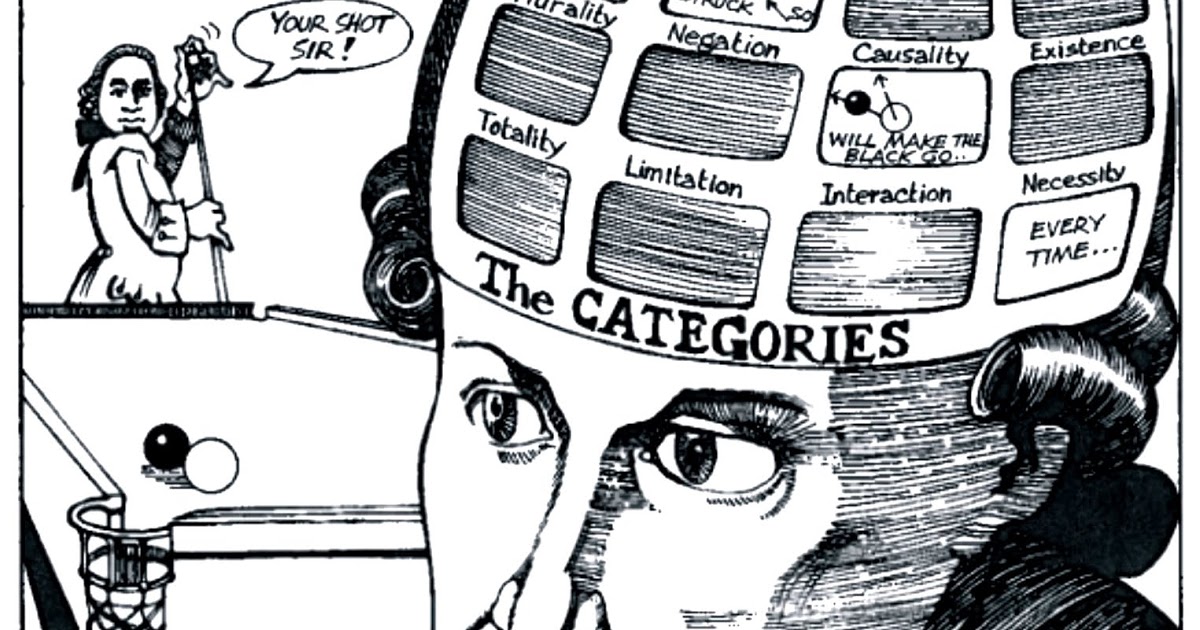

How do we treat the understanding of knowledge, between the relationship of our consciousness and the object of view? How do we construct the epistemological grounds of knowing? During Hegel (1770–1831) time in the 19th century, contemporary philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) published his work on The Critique of Pure Reason (1781), drawing a distinction between subject (‘I’ness) and object. The object exists in-themselves, regardless of the subject. It is we, the subject of experience, who gives the object meaning from our senses. The object exists for us, for the experiencer. Kant argues that there are properties in the object which exist in the object itself outside from our senses, in the external world. The object’s practical end is subordinate to the demands of the rational will, unable to proceed further. This concept is similar to Plato’s idea of Forms where there’s a perfection of object that transcends time and space, existing in the Realm of Forms. i.e. Forms of apple, Forms of knowledge, Forms of love, etc… Plato (429?–347 B.C.E.) accepted teaching from the pre-socratic philosopher, Pythagoras (570? to 490? BCE), positing that abstract form of mathematical objects is the ultimate truth, the perfect Form.

Hegel disagrees with the Pythagorean. Mathematics only touches the surface of the object, but it never reaches in to the depth of the lived experience. If we break a concept in Math into its inner notion, the breaking down of concept can be seen as not-true (false) because the inner notion has no relation to the concept itself. Only when put back together with the inner notion into its unity as a whole can we consider it as truth. The process of putting back together is necessary to go through with, but it cannot grasp what is left behind, it cannot grasp the synthesis of experience. Math superimposes a material sense onto self-consciousness. Hegel’s solution is the dialectical experience; the meditation between the first principle to the second principle. But to give meaning to an object, we, the phenomenological observer, need to understand the structure of consciousness. The process of inferring a logical determinateness (rational discourse) through the subject as I, to the object.

We have to reject everything to do with other belief and our own. 1) Cartesian doubt & 2) Polonius Enlightenment. 3) Using Socratic scepticism position is to reject determinate interpretation and to continue contemplating and waiting for the next idea or interpretation to show up only to reject it again, leading one to take the contradictory position of nihilism. 4) An easy path out of absolute knowing is accepting the vanity of consciousness and to re-cause consciousness back to itself, pursuing a false sense of truth for its own satisfaction.

Hegel wants us to accept learning as suffering in order for us to transcend knowledge beyond consciousness own limitation. We recognize that by interacting with an object, we are entering with certain presupposition. We distinguish the object as something for consciousness and also something distinct from us. Then, how can we determine this assumption? Building from Fichte (1762–1814) concept, we start by viewing reality through the lens of the individual capacity for freedom (viewing from the lens of the object is to give the object determinism with the inability to transcend its own deduction). We have to presuppose that we are free to be conscious and use this as first principle. The ‘I’ with my consciousness of freedom view the object that is existing for consciousness but also outside of consciousness in the ‘Here’ and ‘Now’. To posit/transcend from this level, I have to do it from my consciousness. Consciousness relates to object and to itself to transcend itself. This relation is not a ‘third entity’ in the sense of Plato’s Republic nor in the Bible, but it is consciousness itself. The objectivity of the object for consciousness dissolves into subjectivity as it sinks into the level of consciousness to the level of its way of knowing it; encapsulating the infinite as finite; to bring order out of chaos, and to do it repeatedly to transcend itself from each moment. The ‘I’ freely posit itself as ‘I’.

Consciousness is not aware of its own transcendence. It is we, the phenomenological observer, behind the curtain of consciousness, who is observing the transcendence from one shape of consciousness to the next, observing its contradiction & failure, its negative determinateness. Thus, for Hegel, learning is a Way of Despair; it is its own suffering. The truth or absolute knowing is the endpoint of the ladder of consciousness, where being & thinking are same, being-for-consciousness & the thing-in-itself are one. But by interacting with the object, the ‘otherness’ (distinctiveness properties) appears to the surface. It is no longer the truth and needs altering. Otherness exists as an innate idea, first principle and transcendental God, and it is our duty to uncover its mysteries with seriousness only to negate this knowledge in the next moment.

Experience, is a means to a means, potentially never-ending, mediating each moment. Chasing the truth in absolute darkness (or absolute lightness).